By Staff

What intellectual “postcard” should we choose to send ourselves from any great repository of history? Several of our Electrum Magazine staff-members (Patrick Hunt, A.C. Williams, P.F. Sommerfeldt and Melissa Guertin) were at the British Museum this past week (late March 2011) – and some of us for five full days! – where we couldn’t help but view many of the iconic objects in these two books reviewed below. While the galleries are fresh in our minds, this pairing of books makes for an apt reminiscence, mindful that the authors’ and our own interpretations of the objects may all be idiosyncratic. Since our subtitle is “Why The Past Matters”, we much appreciate these deservedly acclaimed books.

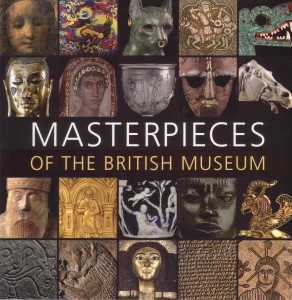

Masterpieces of the British Museum, edited by J. D. Hill (British Museum Press, 2009, 2010 reprint) presents 250 objects across 10 arbitrary categories, symbolically one object per year of the British Museum’s 250 year existence. Some of these categories include “Seeing the Divine”, “Rulers”, “Death”, “Mythical Beasts”, “The Human Form”, “Eating and Drinking” and “Animals”. Since there are 6 million objects, drawings and prints in the museum, a rational scheme for choosing these relatively few – each given a separate page – is justifiable for either the social importance of the object selected, how striking or how representative it is for any given culture.

Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum since 2002, followed his recently concluded blockbuster BBC Radio 4 broadcast series with his best-selling book A History of the World in 100 Objects (Allen Lane, 2010), in no small part also showcasing the British Museum collections as a first rate world museum, likely without parallel. As MacGregor notes for his brilliant book, each object highlighted and accompanied by a superb photograph was chosen not for mere (if at all) visual impact but rather how each object drew on or reminded of a larger historical theme. This overarching idea appears to work well even if the object in view is out of its original context because it is now in a world context in the museum. MacGregor’s thesis also means telling history through “things” rather than via “texts”, contrary to lexicographer Samuel Johnson’s old dictum that “all we need to know of history we know through books” and as such, each individual object story told explores human history as a “poetic re-creation”. MacGregor’s bold schematic – inspired in part from a challenge by BBC Radio 4 for a comprehensive history of the world narrated from the British Museum – includes some rather obscure, small yet fascinating early art objects such as the 10.2 cm stone Ain Sakhri (Israel) “lovers” from c. 8000 BC and the 20.7 cm mammoth tusk “Swimming Reindeer” carving from the Late Magdalenian Stone Age circa 12,500 years ago from the Montastruc Rock Shelter, Tarn et Garonne, France.

Many of the most popular British Museum objects, however, are accounted for in both books. These include the Rosetta Stone, the Assyrian Nineveh Friezes, the controversial silver Warren Cup and astonishing glass late Roman Lycurgus Cup, the incomparable Pheidian Parthenon Sculptures (“Elgin Marbles”) from around 435 BC, the medieval Lewis Chessmen, Durer’s 1515 Rhinoceros woodcut, a Lower Paleolithic Olduvai basalt chipping tool, circa 1.8 million years ago and the clay Cyrus Cylinder (we hope, not holding our breath, that it will be returned from Iran) from around 530 BC. In Hill’s Masterpieces Chapter 3 on “Rulers”, is the stunning Sutton Hoo Helmet, hammered of iron and trimmed with tinned bronze, excavated from the ship burial of an Anglo-Saxon king from around early 7th c. AD. In Masterpieces Chapter 4 titled “Violence and War”, one expects to see the Exekias Black Figure vase, c. 540 BC, depicting the tragic myth contest between Achilles and Penthesilea, and the reader is not disappointed. Here also is the Battersea Shield, circa 350-50 BC, found in the Thames River at Battersea Bridge with its aesthetic precursor to Art Nouveau in its riveted decorative swirls and red glass inlays, also worthy of note for amazing Celtic metal craft even if it was not meant for battle. Chilling because it is a too-contemporary artefact of war is Cristovao Canhavato’s Throne of Weapons constructed of decommissioned weapons – mostly gun parts – from Mozambique’s civil war. Our staff favorite both to see and read about on this war theme is the grotesque, flamboyant crocodile armour (cuirass and helmet), 3rd c. AD., from Roman Egypt, preserved in the desert but now restored with all its near impenetrable eccentricity. Having protected its original animal on whom it slowly grew, this crocodile “kevlar” must have at least lasted to seemingly protect at least one Roman soldier abroad who may have also been a member of an Egyptian crocodile cult. Now it enlarges the imagination of all who view it as more than a curiosity of history.

While the last chapter of Masterpieces, “The Power of Objects” is eclectic, one of the seemingly humbler objects highlighted – alongside the immensely famous Portland Vase, the Standard of Ur, the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser and Hokusai’s ‘Under the Wave’ woodcut – is also one of the most poignant: a simple rag doll also from Roman Egypt, circa 1st-5th c AD and 19 cm long. It is of “coarse linen stuffed with rags and pieces of papyrus” and most simply decorated, essentially faceless but all the more meaningful. Possibly profound because although seemingly not meant to last, it has ended up less ephemeral than its original human owner, a once warm-blooded child who is now dust. In the words of Shelley’s Ozymandias, “Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair.” Or at least, memento mori, be duly reminded of mortality and the accident of any posterity whatsoever. This is, of course, most illustrative of the responsibility of a great institution with a vast collection of human artefacts to always bow to the Muse of History, the inspiration of all museums.