by Melissa Guertin

Edvard Munch may not now be screaming over his work’s repeated purloinings (1995, 2004) from several museums, since they’ve been returned, but Isabella Stewart Gardner should be turning over in her grave because the 1990 heist of twelve masterpieces from her lovely Boston palazzo museum is still sadly unresolved; Ulrich Boser’s entertaining book The Gardner Heist (Smithsonian 2009) on this mystery is a page turner. According to most estimates art theft is proliferating like a plague; Frank Browning’s 2007 NPR article “Stolen Fine Art: Organized Crime’s New Commodity” rated art theft as the third most lucrative criminal activity after drugs and arms trafficking, documenting up to $6 billion a year just a few seasons past. Fact may be stranger than fiction after all, but art theft novels that mirror reality may be closer to the truth than is comfortable.

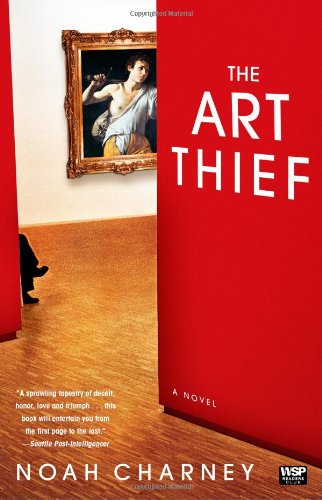

Who better than an art historian and expert in art crimes to write a novel regarding art theft and forgery? Noah Charney does just that with his quirky debut novel The Art Thief (Atria 2008) although seemingly all agree his acclaimed Stealing the Mystic Lamb (Public Affairs 2010) on the Van Eyck Ghent Altarpiece is by far the best available book on the story of the most-stolen iconic work in history. For the most part, Charney’s novel The Art Thief – a staff pick at the Stanford University Bookstore – is a vividly narrated story about a series of crimes involving famous masterworks in a money-and-ego driven market, a noir but plausible world of art where things are not what they seem behind the glam and glitter.

The plot centers around three paintings stolen in seemingly unrelated episodes: a Caravaggio Annunciation from a church in Rome; Kasimir Malevich’s White on White from the Malevich Society in Paris; and a similar painting by Malevich from the National Gallery of Modern Art in London, which it recently purchased at auction for over six million pounds. Charney further complicates the plot by adding twists including overpainting, forgery, and deception. As this reader (educated in art history) delves into the mystery further, she finds that little is really as it seems and that these stolen paintings are, in fact, very much related. Fortunately, Charney paces the story well enough that each storyline is easy to follow. He easily transitions from one storyline to the next, providing a good flow between scenes, each of which carries the narrative with miniclimaxes of dramatic tension rising at just the right moments. Additionally, Charney provides the reader with subtle clues and hints to help piece together bits of information and relationships between and among the characters.

The plot centers around three paintings stolen in seemingly unrelated episodes: a Caravaggio Annunciation from a church in Rome; Kasimir Malevich’s White on White from the Malevich Society in Paris; and a similar painting by Malevich from the National Gallery of Modern Art in London, which it recently purchased at auction for over six million pounds. Charney further complicates the plot by adding twists including overpainting, forgery, and deception. As this reader (educated in art history) delves into the mystery further, she finds that little is really as it seems and that these stolen paintings are, in fact, very much related. Fortunately, Charney paces the story well enough that each storyline is easy to follow. He easily transitions from one storyline to the next, providing a good flow between scenes, each of which carries the narrative with miniclimaxes of dramatic tension rising at just the right moments. Additionally, Charney provides the reader with subtle clues and hints to help piece together bits of information and relationships between and among the characters.

Although there are many characters and each one is vividly described, none are fully developed. If at times they seem caricatures, especially the French detective Jean-Jacques Bizot with his porcine appetite of Rabelaisian proportions, fortunately Charney’s art capers keep the pace going and the reader involved. Both of the main female characters, Geneviève Delacloche and Elizabeth Van Der Mier, the curator at the Malevich Society and director of the National Gallery of Modern Art respectively, are almost interchangeable personality-wise, coming off as brusque and exasperated, not surprising given the situations in which they find themselves.

The male characters are more varied in personality, though still not fully realized. Charney only gives us a taste of these characters, never completely revealing their motivations. Gabriel Coffin is an eminent art investigator initially called to assist with the missing Caravaggio. Nothing stands out about his character more than he is extremely well-versed in art crimes and well-dressed to boot. Henry Wickenden, the Scotland Yard inspector who takes on the National Gallery theft, is a brilliant detective who is socially awkward and often disappears into the background. Equally astute as Wickenden, though more corpulent and bumbling due to this condition, is the detective Jean-Jacques Bizot, who investigates the Malevich theft in Paris. In just about every scene when he is not tracking thefts, Bizot is consuming vast quantities of food with his friend, Lesgourges, whom Bizot enlists to assist him to try to solve the case. The rapport between these two friends waxes satirical at times, often over the top like Trimalchio’s Feast, although their ridiculous gluttony becomes a turnoff after awhile. The sarcastic and condescending Professor Simon Barrow is called in to assist on the cases because of his art historical expertise. His constantly snarky comments and arrogant demeanor make him the least likable of the characters.

The most redemptive part of the book is that Charney expertly describes motivations behind art crime, providing considerable insight into this little-known world. One might even think of cockroaches scattering when Charney turns on the light. His adept discussions in the novel on various elements of art history are both informative and fascinating. Charney’s quixotic use of adjectives, similes, and metaphors, however, are distracting at times, making his fiction writing style a bit contrived in places and even didactic, but always accurate and informative. It is evident through his writing that Charney is passionate about both art history and art crimes, which makes this novel all the more compelling. His second book, Art and Crime: Exploring the Dark Side of the Art World (Praeger 2009) is the non-fiction twin without the caricatures.

Overall, The Art Thief is an exciting novel with plenty of plot twists to keep this reader engaged. Although this reader does not get a full sense of the characters’ personae or motivations throughout the story, the intrigue and mystery of the plot were more than enough to keep my attention, making me want to find out just how The Art Thief ended. Charney’s debut fiction effort had me looking forward to reading a more polished although just as engrossing follow up in non-fiction, so I’m eager to read his newest book, Stealing the Mystic Lamb.