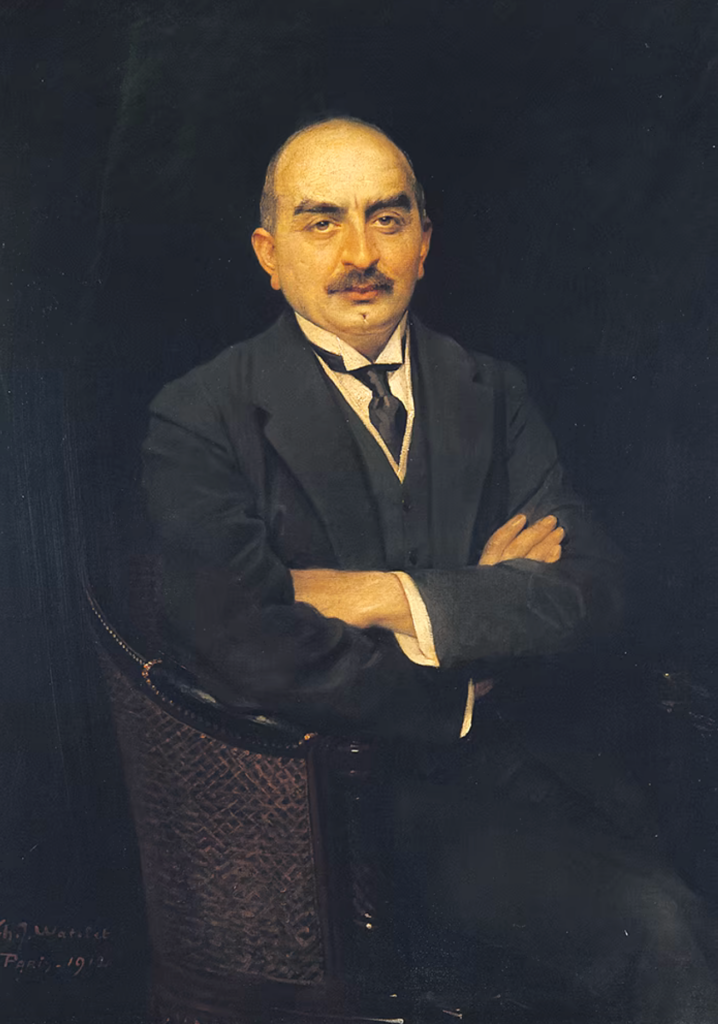

Calouste Gulbenkian in 1912 (Image courtesy of Financial Times London)

By P. F. Sommerfeldt –

In Lisbon in late March I had a list of must visits to Portugal’s beautiful capital city, including the famous Gulbenkian Museum in its private foundation premises. This renowned museum – in modern brutalist style surrounded by lush gardens seen through its windows – is the home for the eclectic art collection of Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian, of which my favorite areas of concentration are the Persian and Near Eastern and European arts, including painting and Lalique glass. The Gulbenkian Museum has some of the finest Persian cultural artifacts and Lalique objects in the world as well as exquisite signature European art pieces by great masters whose appealed to Gulbenkian, often going far out of his way to pursue individual works of art.

Gulbenkian was often considered eccentric as a cosmopolitan Armenian industrialist and collector – his flamboyant father even more so – and the family fortune was widespread including in global petroleum. Calouste lived in Istanbul, Cairo, London, Paris and Lisbon, among other cities, where he cast his net wide for outstanding and often unique collectibles that met his high connoisseur standards, eventually acquiring over 6,400 objets d’art and he sometimes commissioned glass or jewelry art pieces from artists like René Lalique, from whom he owned 140 pieces especially during the Art Deco Period. I’ve selected only just a few (six) of my personal most-liked pieces to highlight here.

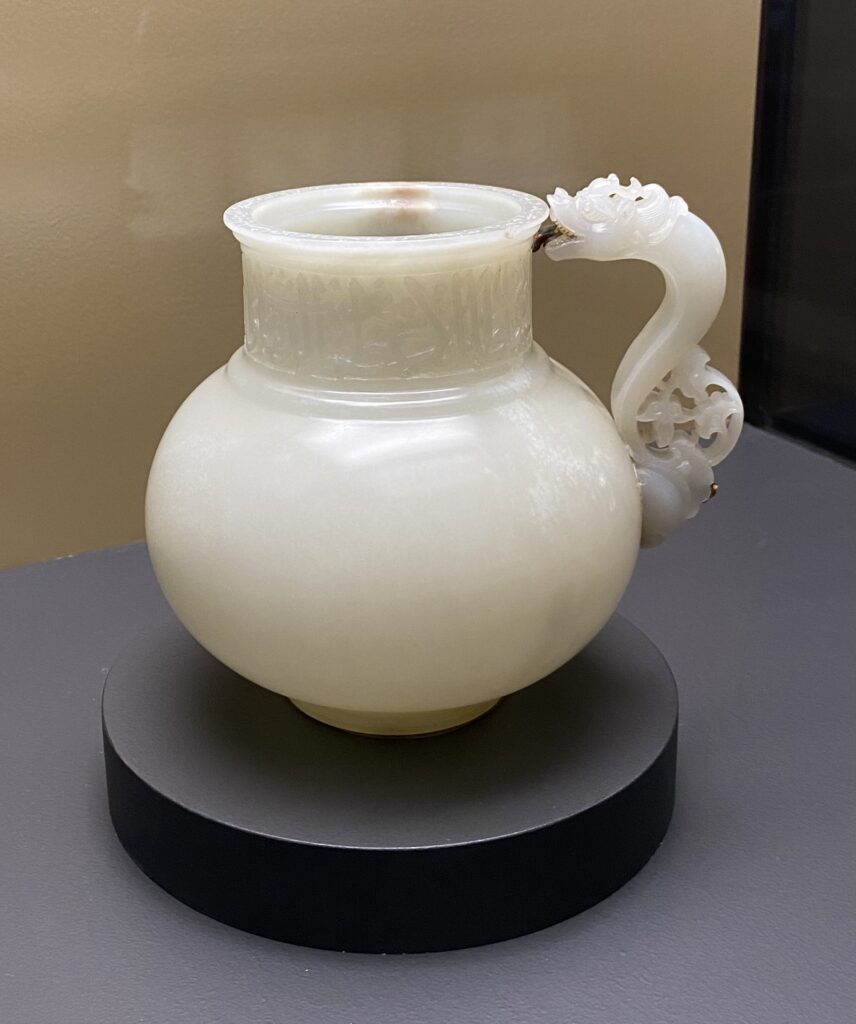

First, near the museum entry point to the incomparable Near Eastern galleries is an exquisite pale white jade Persian Timurid period (early 15th c.) small round jug called a mashraba for cooing drinking water (14.5 cm h). This jade vessel is perhaps most memorable not just for its luster and highly polished surface aesthetics, but equally for its illustrious provenance because it belonged to one of history’s most interesting royal scientists, a prince and then sovereign, grandson of Timurlane himself memorialized by Elizabethan poet and dramatist Christopher Marlowe. The first known owner of this jade object was Ulugh Beg of Samarkand, a mathematician and astronomer who built one of the most fascinating observatories in history ion his city of Samarkand where it can still be seen in refurbished condition.[1] This jade jug later made its way to Mughal India where it then belonged to Jahangir and Shah Jahan of Taj Mahal fame. Their names are also inscribed near its Chinese dragon handle. Perhaps it is easy to understand why Gulbenkian was doubly attached to a beautiful jade vessel whose prior famous owners’ hands held it before he did.

Second, a somber chiaroscuro brown-toned Rembrandt tronie subject of an old man graces the European Baroque painting gallery, its description as Old Man with a Stick (1645) hardly a glamorous title but nonetheless a realistic portrait of old age. From the period just after his beloved wife Saskia died and a tough time when the artist also struggled with her relatives and contentious Amsterdam burghers, few studies of the elderly transcend these serious character studies of Rembrandt.[2]

Rembrandt, Old Man with a Stick, 1645, Gulbenkian Museum (Photo P. Hunt 2024)

If sufficiently emotive to convey any psychological or emotional state of mind, a viewer might see more uncertainly and apprehension in the face of the old man more than anything else as he might be contemplating his future. One might also deduce the stick held is a needed cane or walking prosthesis for a man concerned about his decreasing physical stability. Sold by the Soviet government from the Hermitage in 1950, no less interesting is that this painting once belonged in the royal collection of Empress Catherine the Great of Russia and it became one of Gulbenkian’s absolute favorites according to his correspondence. Apparently exactly this kind of royal provenance intrigued Gulbenkian.

Persian Kashan Timurid 14th c. Glazed Bowl, Gulbenkian Museum (Photo P. Hunt 2024)

Third, a 14th century Persian stone-paste fritware glazed bowl from Kashan with an elephant in its center immediately drew my attention with its dominant turquoise glaze, the elephant surrounded by three flying phoenixes with long streaming wings and tails. Said to be Sultanabad style during Ilkhanid rule, the elephant is stylistically endearing in its roundedness – echoing the bowl shape itself – and if it is not altogether realistic, as if the artist had never truly seen a live elephant, it nonetheless shows care in its detail whereas the surrounding circling phoenixes are more traditional. Whether the accompanying colors along with glossy tin white are derived from cobalt or lapis lazuli, the former more likely, it is nonetheless stunning and arresting with its combination of Indian and Chinese imagery absorbed after the Mongolian invasion when the market could appreciate such cultural hybridity. It was painted first in these bright hues over tin white and then overglazed with a clear protective glaze.

Fourth, a Jean-Francois Millet pastel from ca.1872-3 titled The Rainbow in his characteristic bright color palette against dark sky, a form of landscape chiaroscuro, is one of a Millet pair Gulbenkian purchased in 1920 in Paris, the other titled Winter. The museum catalog suggests it is influenced by impressionism and is one of a study of the four seasons from his Barbizon period of “return to the countryside” after 1849 that subtly emphasizes “the relationship between man and the environment that is so essential to Millet”. [3] One of my best personal venues for Millet is the Orsay in Paris, where his luminous landscapes with or without human presence have a mystical quality bordering on the magical; humans when present are greatly diminished against nature like his The Gleaners where the vast horizon and sky seem to put humans distinctly in secondary place.

J.- F. Millet. The Rainbow, ca. 1872-3, Gulbenkian Museum (Photo P. Hunt 2024)

The Rainbow at the Gulbenkian, on the other hand, shows an almost solitary small darkly-blue dressed, partly-shaded almost irrelevant human in the background against a verdant green spring setting where white blossoms shine on the trees and green plants rise out of the brown soil in rows. Because the light is in the misty foreground with the rainbow between it and the back landscape, the sun is shining in front of the painting with dark grey clouds raining in the distance. The painting also reminds me of Rimbaud’s contemporary poem “Après le Déluge” from his Illuminations ca. 1873-5 for their mutual immediacy.

Fifth, John Singer Sargent’s 1887 Lady and Child Asleep in a Punt under the Willows is as striking as many of his magisterial portraits or studies of women even when they seem deceptively casual or spontaneous. This singular painting, however, is far more an Impressionist statement than his more formal portraits, mostly influenced by his friend Monet with whom he had stayed at Giverney. The light behind the willow tree flashes off the adjacent water since willows love watery habitats- likely the Thames around Henly – and the willow leaves silhouetted above the water have the special ephemeral quality of masterful Chinese brushwork. Mostly in shadow, the woman and child asleep in dappled light are encircled by the willow branches and trunk, dramatized by the broad red pillow or blanket behind them on the boat against the contrast of blue or sunlit water. Singer Sargent should be more often credited with being a central force in British Impressionism as PImental argues, and this painting loved by Gulbenkian who had more of a penchant for portraiture [4] is one of the era’s statements of Dolce Far Niente, “sweet do nothing” even if the woman and child are not napping.

John Singer Sargent, Lady and Child Asleep in a Punt Under the Willows, 1887 Gulbenkian Museum (Photo P. Hunt 2024)

Singer Sargent even painted people idling by an alpine stream in the Valle d’Aosta with this exact title, as I’ve viewed in the Brooklyn Museum, purchased from the English Art Club of London in 1909. Gulbenkian purchased his Lady and Child Asleep…via Sotheby’s at Colnaghi in 1921. I loved the recent (2023) San Francisco Fine Arts Museum Singer Sargent exhibition of his work in Spain. Our daughter who also urged us to visit the Gulbenkian – now a director of an arts museum in Canada – knew John and Flavia Ormond very well in London (he was the grand nephew of Singer Sargent) and we spent an dinner evening with them in their Chelsea home. Singer Sargent is beyond doubt one of the most influential artists of the 19th-20th century and more and more appreciated as time passes. When I worked on New Bond Street for Philips Son and Neale Art Auctioneers (now Bonhams) in the late 80’s, through earlry ’90’s I could never see enough Singer Sargents in the UK and I also frequently pore over the wonderful book by Donna Lucey, Sargent’s Women: Four Portraits Through the Canvas (2017).

René Lalique, Dragonfly Lady Corsage Ornament, ca. 1897, Gulbenkian Museum (Photo P. Hunt 2024)

Sixth and final, like so many other admirers I adore the Gulbenkian Lalique collection’s “Dragonfly Woman Corsage” pin from 1897-8 as one of the most imaginative pieces of hybrid forms and exotic composite jewelry ever conceived. Made of gold, opaline enamel, chrysoprase, chalcedony, moonstones and diamond, it features a dragonfly body with diaphanous wings surmounted by a woman’s green upper torso and helmeted head emerging form the dragonfly’s mouth as if in metamorphosis. The woman’s helmet (Athena-Minerva or an Amazon?) is formed by two facing enameled blue-green beetles, a coloration paralleled in the diamond-encircled cells of the lacy wings and on the abdomen and dragonfly tail segments.

The Gulbenkian’s own description of this corsage pin (23 cm long) also finds it a fascinating creation: “The hybrid figure…at once beautiful and horrible” is noted as “Without doubt one of the most spectacular pieces of jewelry ever created by René Lalique, the great modern jewelry artist,” and I so thoroughly agree with its stunning and hyperbolic contrasts. I can barely fathom how broad and detailed was the brilliant imagination of René Lalique so playfully demonstrated in this unique piece.

While so many other Gulbenkian treasures could equally demand description, I rest my case on these magnificent few as having so piqued my interest in Lisbon.

Notes:

[1] Ulun Begh of Samarkand. Kulikovskij, P. G. (October 1981). “Book Review: Science at Samarkand: From the History of Science in the Time of Ulugh Beg”. Journal for the History of Astronomy.12 (3): 211–12

[2] Patrick Hunt, Rembrandt: His Life in Art. New York: Ariel Books / San Diego: Cognella, 2006 (2nd ed. after 2007), 14,17,19, 25.

[3] A. F. Pimentel. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum: Director’s Choice. London: Scala Arts, 2023, 65.

[4] Pimental, 70