Nikolai Rerikh, Guests from Overseas, 1901, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (public domain)

By Patrick Hunt –

Vikings in the early medieval period have often been odiously depicted as bloodthirsty and berserk raiders, certainly justifiable at times given the infamous Lindisfarne raid event of 793 on England’s northeast coast, with other details of raids around 991 recorded after the fact from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle compiled from the 9th to 12th century and Saxo-Gramaticus’ Gesta Danorum of the 12th century, among other strident accounts. Yet a long history of challenging but adaptive maritime life and Viking intrepid seafaring and exploration made their wide-ranging movements possible. For whatever multiple reasons the Old Norse Vikings began to move out of what is now Norway, including desire for luxury trade goods, burgeoning population due to warming climate and looking for better farmlands, late 19th and early 20th century archaeological discovery and subsequent preservation of 9th c. Viking ships like the Oseberg and Gokstad, now conserved and housed in the Vikingskipshuset (Viking Ship Museum) in Oslo, Norway, present astonishing seaworthy craft in great detail even after burial for more than a millennium. Also, the Roskilde Vikingeskibs Museet in Denmark offers additional Viking Ship material recovered from deliberate sinking of multiple ships now reconstructed.

Viking Expansion From ca 820-1000 CE (public domain)

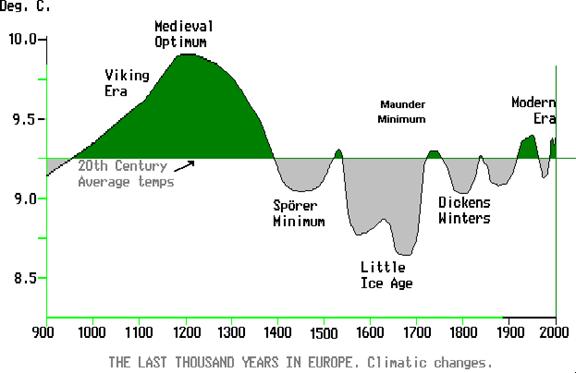

A warming climate led the Vikings (from vikingr, “sea rover, freebooter, pirate, one who came from the fjords”) south and west from the rugged inlets and coasts of Norway as ice thaw, longer seafaring seasons and other overall better weather factors made for longer periods of exploration. Having endured and even mastered the worst of navigable circumstances, Vikings found ample opportunity to extend their wandering into more hospitable climes. Their strong ships, if the ship burials of chieftains and kings like Oseberg and Gokstad are comparable, were capable of handling some of the roughest ice free navigation even around the Arctic Circle as the northern coastal cities of Trondheim (63 degrees latitude north) and even Tromso (69 degrees latitude north) were explored by their traders as early as the late 9th century. Tromso was founded as an outpost by the Norse chieftain Ohthere around the 890’s – although not necessarily Viking – but Trondheim was founded as Kaupangen (“trading place”) in 997 by Viking king Olav Tryggvason although the earlier Viking king Harald Harfagre held assemblies for all freemen there in the mid-to-late 9th c. That the Vikings also voyaged to North America (“Vineland”) via Iceland and Greenland to Newfoundland – and possibly even to Massachusetts as National Geographic’s Sarah Parcak has suggested by LiDAR satellite archaeology – is now more widely appreciated than ever before, easily half a millennium before Portuguese and Spanish explorers. Viking ship burials for kings and chieftains give us fortunate glimpses into such sturdy sea craft that made long sea voyages possible. One of our best relatively contemporary sources about Viking shipbuilding is the 13th c. account of the Icelandic poet Snorri Sturluson in his Heimskringla (partly the Saga of Olav Tryggvason).

Basic European Climate Graph Representing 900-2000 CE (public domain)

Oslo’s Vikingskipshuset on Bygdoy peninsula west of the city center is a must for anyone curious about maritime history, certainly the best preserved, documented and displayed ships in the Viking world. Much of what we now know about Viking ships derives from the continuing research at this world-renowned museum also known as the Kulturhistorisk Museum, connected to the University of Oslo. At least a half million visitors see these ships annually as one of Oslo’s and Norway’s most significant sites. The following fascinating details of the two main Viking ships show why they deserve attention, along with other subsequent Viking ships at Roskilde, Denmark.

Oseberg Viking ship, Vikingskipshuset, Oslo (public domain)

Oseberg Viking Ship

The Oseberg Viking ship was found on rural property by farmer Oskar Rom at the Lille Oseberg Farm at Slagen in Vestfold County on the Oslo fjord’s west side, south of Oslo, in 1903 in a large burial mound of either royal elites or highest chiefly members from around autumn of 834 when buried. This date is based on dendrochronology of the associated burial mound wood, although the two skeleta found in the burial mound are of elite females (one elderly and one younger), along with richly decorated wood sleighs, leather, rich textiles including wool and even silk, a chariot and copious food supplies and skeleta of 14 horses, an ox and 3 dogs. Five unique intricately carved hardwood animal heads, possibly handheld, were also found in the burial, several with silver rivets and possibly attached to now missing much longer (metal?) objects up to 50 cm long. It is commonly now suggested that the elderly woman buried was Queen Asa, grandmother of King Harald I Farhagre (ca 850- ca 932), the first celebrated king of all Norway, and mother of the Vestfold King Halfdanr Svarti (810-60). The ship remains took at least 21 years to restore along with the finds, after extensive long periods drying out the artifacts of wood and other materials. As of today, over 90% of the ship’s wood is original (the museum differentiates the additions with distinct coloration).

Oseberg Prow detail in carved wood including serpentine (drekkar) bow (public domain)

The highly-symmetrical Oseberg ship was 21.58 meters (about 70 ft) in length, 5.1 meters (almost 17 ft) wide and mostly of oak, with a pine mast approximately originally 10-13 meters (at least 32 feet) high and a beautifully-carved coiled spiraling serpentine prow. Thus its sail would have been about 90 sq. meters (nearly 1000 sq. ft) and its speed could have been up to about 10 knots (11.5 miles) per hour in good wind. The ship had 15 pine oar hole pairs, thus 30 oarsmen plus helmsman and lookout and not including elites. The date of the ship is at least from around 820 as determined by oak dendrochronology. The karve (“longship”) as excavated 1904-05 by Haakon Shetelig and Gabriel Gustafson and has klinker construction (klench is an old Teutonic word meaning “to fasten together” although not a Viking word), meaning its 12 (each side) hull oak planks overlap in what is called “lapstrake” for tight seaworthiness fastened with iron rivets. Each hull plank strake has at least 2-3 centimeters in tapering thickness below the waterline and thicker above. The deck had movable loose pine planks for adjustable placement. Whether the Oseberg ship had substantial sailing history is unknown, since it was built for elites, but its ornate woodcarvings along its prow and and keel depict masterfully crafted “gripping beast” motifs. Built in the southwestern Norway region where it was found, the Oseberg ship could be sailed or rowed depending on conditions and proximity to coasts and harbors.

Carved Oseberg oak keel with elaborate running gripping beast motif (public domain)

The Oseberg Viking ship was also carefully examined digitally in 2005 and since such that computerized research shows even more details of Viking shipbuilding craft than was previously known in the 20th century.

Carved hardwood animal head (one of 5) in Oseberg Ship Burial (public domain)

Gokstad Viking Ship

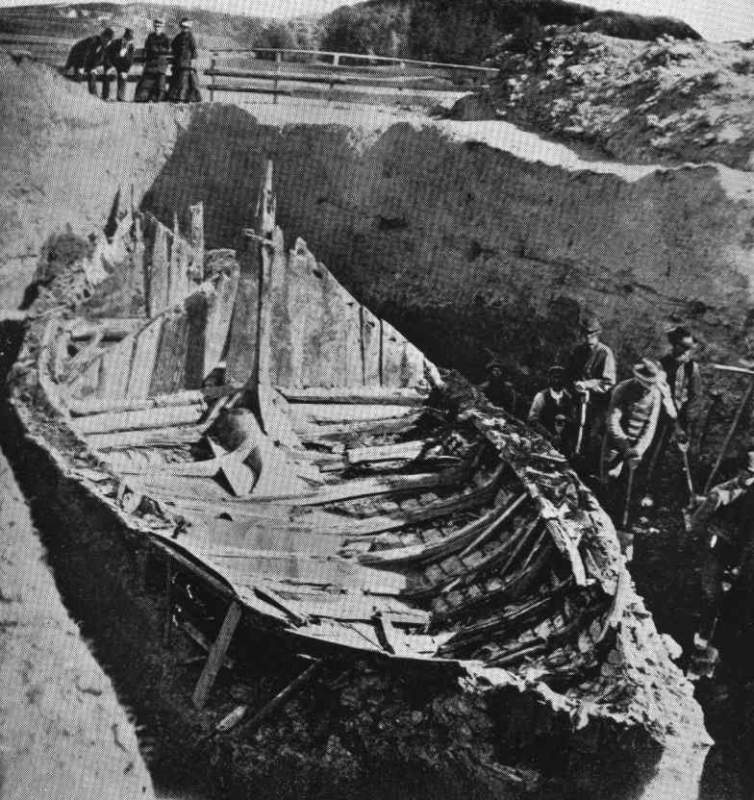

Similar in many ways to the Oseberg ship, the Gokstad Viking ship and its burial dates to 890, a little later than the Oseberg but discovered earlier in 1879, setting precedents for the Oseberg excavation. The large burial mound on Gokstad farm was long known and called the “king’s mound”; Gokstad farm boys digging in it found enough ancient material so word got out and Norwegian archaeologist Nikolaysen from the University of Oslo began proper excavation in 1880. The mound had enough artificially-accumulated clay and peat to extend 45 meters (147.5 ft) in diameter and still 5 meters (16.5 ft) high even though it had lost significant height over the centuries, leaving some of the ship exposed over the centuries or only covered in shallow clay and peat, which impacted the preservation of this upper Viking ship, since it lost its prow and stern and two highest strake planks. The excavation dismantled the ship, subjecting the strake planks and other well-preserved wood to intense steaming to bend back into original curved position before reassembling. New oak wood has replaced the lost parts in the re-assemblage also now on display at Oslo’s Vikingskipshuset.

Gokstad Viking Ship, Vikingskipshuset, Oslo (public domain)

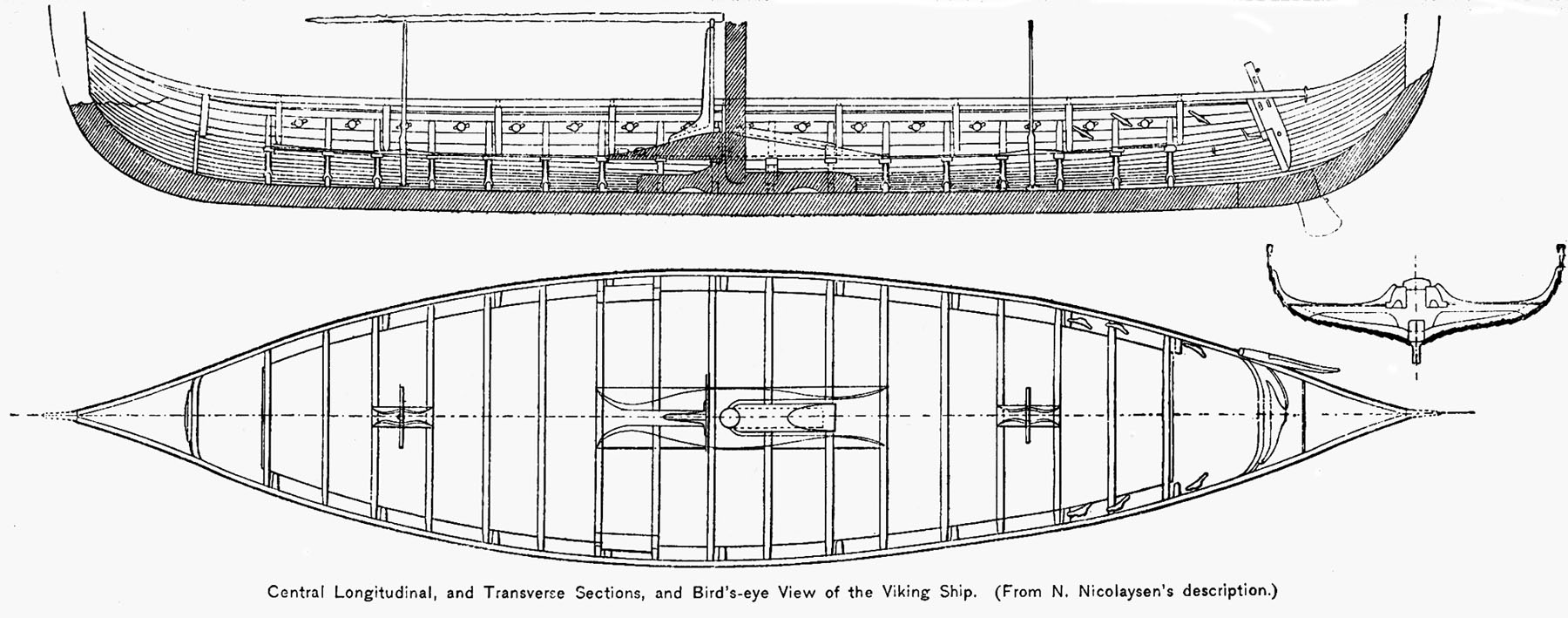

Slightly longer and wider than the older Oseberg Viking ship – but with equally astonishing symmetry as seen in the above photo – the similar oak-built Gokstad is 23.2 meters (78 ft) long and 5.2 meters (a little more than 17 ft) wide; having a pine mast but not enough survived to estimate its original height, although probably at least 10 meters high like the Oseberg given the similar diameter of the mast stump (with likely similar full sail dimensions of 90 sq. meters or 1000 sq. ft). The Gokstad also had pine oar pairs, with 16 pairs so that 32 oarsmen would have rowed the ship when not under sail. It had 16 rows of lapstrake planks, therefore deeper or higher off the water than the Oseberg – with 9 strakes below the water line – and constructed with an entirely oak keel. Unlike the Oseberg, however, the Gokstad had been buried with 32 shields fastened along the top of the rail, even with remnant colored (yellow and black stripes) cloth on some shields and fragments of wool and red colored fabric of possible remnant sail found on the ship deck, which was covered with loose pine planks that could be shifted for seating, like the Oseberg. This Viking ship was a richly-decorated and well-crafted vessel, again unknown how much actual maritime use it saw, since the pine oars, like those of the Oseberg, had only fractional wear and may have been made expressly for the ship’s burial. We can only speculate on the decorated prow – dragon or serpentine or similar beast ? – since neither bow nor stern survived above ground. Like the Oseberg, the Gokstad Viking ship – its similar karve longship overlapping planks also fitted with iron rivets – could have sailed up to 10 knots (11.5 miles) per hour and was strong enough to endure tough sailing conditions in rough seas, therefore seaworthy over great distances in challenging open water oceanic conditions.

Gokstad Farm, Gokstad ship excavation circa 1880 (public domain)

The single rich male human burial was in the stern of the Gokstad, with grave goods befitting elite status in a purpose-made burial chamber of birch bark strips. Quality linen made up the bed and other textiles included silk with interwoven gold thread. The man buried was tall – a little over 181-3 cm (6 ft) – and probably around 45 years old at death. Cause of death was likely in battle given the deep cut on the right calf bone and deep cutting blows to the lower legs resulting in heavy bone damage, possibly from axe or similar blade. Buried with the elite man – possibly a royal or high chieftain given the wealth in the grave – were 12 horses, 2 goshawks, 2 exotic birds (peacocks) and 8 dogs. While the identity of the elite man buried in the Gokstad is not known nor possibly connected like the Oseberg ship burial, given the wealth of the ship itself and the burial goods that remained, it is not unlikely that he was of comparable royal status, especially when it is almost certain both Viking ship burials had been robbed out of more precious items like most of the gold and silver artifacts centuries past.

Gokstad Ship schematic drawing from 19th c. (public domain)

A third burial mound clinker Viking ship now at Oslo’s Vikingskiphuset, the Tune Ship, is perhaps less relevant for this study partly because it was “excavated” in 1867 before proper archaeological principles had been formulated and tried; the oak Tune ship is not as well preserved – although its mast support was stronger – and its sail likely also spread to 100 sq. meters. Its associated burial grave was improperly excavated and recorded and much of its remains are lost. Its known details include a length of 18.7 meters (61 ft) long, 4.2 meters (about 14 ft) wide, and it had 12 lapstrakes, 12 oar holes, thus at least 24 oarsmen plus helmsman and lookout, and it was built around 910. No oars were included in the Tune ship and the elite man’s burial and the depleted grave goods, while including 3 horse skeleta, were either mostly robbed out centuries ago or simply did not make it into the archaeological record and preservation. Only a few weapon fragments and chainmail bits, beads and some cloth, leather and wood survive from the burial.

The burial of elite Vikings in beautiful ships makes immediate sense for the afterlife voyage and because of the ever-present reality of the sea in Viking life, since sea travel was not only the best means of transportation, it was a direct correlation of “live by the sea, die by the sea” in both location and agency: the sea was the Viking pathway of life.

Roskilde Danish Viking Ships

Additional Viking ships preserved at the Roskilde Vikingeskibs Museet in Denmark provide needed information about other kinds of ship construction and activity, since the Roskilde ships were not associated burials of human elites like at Oslo but deliberate ship sinkings. John Hale’s Scientific American article “Viking Longship” (Feb. 1998) is a useful guide to the longest Viking ship, the Roskilde ship (35 meters, 115 ft.) and its discovery. Although a little later in date and less preserved than the Norwegian ships already discussed, a fuller picture can be presented by these Roskilde ships, among others. At Roskilde at least five or six Viking ships were sunk with rocks in harbor contexts partly for blocking and shaping the Peberrenden channel at Skuldelev, about 12 miles north of Roskilde, Denmark, their current museum home since their discovery and recovery in the 1960’s and beyond. The Roskilde Viking ships are named Skuldelev 1-6 from their find spot but are quite different. Three types of longships in Old Norse literature, for example, such as the 13th c. Hrlfs Saga (“Saga of Rollo”), can be distinguished: snekke, drekkar and skeid, but these may sometimes be arbitrary descriptive terms partly based on their prows and how elite their masters were, although snekke “thin and projecting” can be understood as a smaller (length commonly around 17 m or 56 ft) longship that could be beached without a port. In contrast the drekkar “dragon” were for elites and highly carved, often with the distinguishing dragon prow that made them stand out as royal or chiefly vessels. The above Oseberg ship is categorized as a drekkar in terms of its decoration but a karve in terms of its size. A skeid, meaning “to cut through water”, is usually a larger longship often up to 30 meters (98 ft) long with 30 rowing benches for 70-80 oarsmen and leaders who were then warriors on the battle ground. In addition, useful terms like kaupskip clearly reference the purpose being for trade rather than war conveyance or other transport. These terms can often be ambiguously interpreted since they are mostly literarily derived from sagas, epics and skaldic verse.

Several of the Roskilde Viking Skuldelev ships are skeid warships, others are actually for transport only or for trade, such as a knarr merchant ship, often smaller than a longship – although up to 16 meters (54 ft) in length – but also often wider and deeper; where carrying capacity of goods is more important than warriors and where speed is not the most vital aspect. The byrding is another light freight Viking ship. Oak is the most important wood for Viking ships depending on availability, and some were made in Ireland of oak rather than Scandinavia. While some of the Roskilde Viking ship hulls were constructed almost entirely from oak, others also have pine, birch, lime, ash and alder (the latter four woods often patchwork) and places of origin range from western Norway to Denmark and even Ireland. The Roskilde Skuldelev 2 is an oak-built war skeid made in Ireland sometime around 1040 with 60 oars, not terribly well-preserved but possibly capable of up to 17 knots (19.5 miles) and built for a chieftain (or royal). The largest Viking longship that has survived even partly (only at around 20% but the oak keel alone is 32 meters long) is also from Roskilde fjord, recovered in 1997 and named the Roskilde 6 at 37 m (121 ft) long and dating from around 1025. It would have held 39 pairs of oars based on the distance of at least 80 cm between ribs. It is narrower than many skeids at an estimated 3.7 meters (12 ft) wide and is an oak ship (at least what has survived).

Roskilde 6 skeid longship on loan, display frame preparation in London for Viking Exhibition (public domain, also courtesy of British Museum)

The Vikingskipshuset Kulturhistorisk Museum in Oslo, Norway and the Vikingeskibs Museet in Roskilde, Denmark carefully document much of the findings from different Viking ships and record the kind of ship movements around the Norwegian coast, the Danish Baltic and beyond, providing a rare material glimpse into Viking seafaring and seamanship of the early medieval world when Vikings were at their zenith of exploration, also the closing days of their Pre-Christian Old Norse religion and world view, a life close to the sea which celebrated brave journeys to the furthest reaches where the sun rose and set over ever distant horizons.

Iceland Spar “Sunstone” for Navigation?

A final navigation note may be also highly relevant. If we can accurately identify the Viking sunstone (solarsteinn in Old Norse) – there is still considerable debate – the Vikings were possibly able to navigate even in the often cloudy skies due to an unusual aid: they used “sunstones” perhaps better known in modernity as Iceland Spar, a form of transparent calcite (CaCO3) crystal whose double refraction phenomenon made it possible to find the sun in the clouds through the crystal by polarizing the light. Sunstones would have allowed Viking longships to wander far from Scandinavian or other coasts into open water for as many days as necessary on the ocean.

Iceland Spar silfurberg calcite crystal – Viking sunstone use?

Known in Icelandic as silfurberg or “silver rock”, Iceland Spar cleaves easily into rhomboidal crystals. One of the difficulties in proving the Vikings used Iceland spar sunstones given only mention in literary Icelandic medieval texts like Raudulphs Pattr, is that it isn’t found archaeologically until 1592 in the sinking of the Elizabethan vessel Alderny and subsequent discovery in the Channel Islands in 1977. Nonetheless, the possibilities are strong since the magnetic compass had been used in Europe only since around the 13th century whereas Iceland was a Viking stronghold since the second half of the 9th century, about the same time as the Oseberg and Gokstad Viking ships.

A brief excerpt from Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla (Saga of Olav Tryggvason, translated by Samuel Laing, 19th c.) concludes with an almost visual image of Viking ships en masse under sail, which may have brought fear to some watching but certainly pride to others:

“The skald must now a war-song raise,

The gallant active youth must praise,

Who o’er the ocean’s field spreads forth

Ships, cutters, boats, from the far north.

His mighty fleet comes sailing by, —

The people run to see them glide,

Mast after mast, by the coast-side.”

(Note the author has a Ph.D. in Archaeology, is a National Geographic Society Grantee, a National Geographic Expedition Expert for Norway in June 2017, and a keynote speaker for Humanities West’s “Age of the Vikings: Wanderlust” event lecturing on “Viking Legacy”, 7:30 pm, Friday, February 24, 2017 ” as well as lecturing at the Stanford Society of the Archaeological Institute of America, 8 pm, March 31, 2017 on “Viking Ships of Oseberg and Gokstad”.)

Notes and Sources:

Vikingskipshuset, Oslo Kulturhistorisk Museum, University of Oslo (http://www.khm.uio.no/besok-oss/vikingskipshuset/).

A. W. Brogger and Haakon Shetelig. The Viking Ships, Their Ancestry and Evolution. London: C. Hurst and Co. (tr. Katharine John). 1971.

T. Davenport and R. Burns. “A 16th century wreck off the Island of Alderney. The archaeology of ships of war.” The International Maritime Archaeology Series 1 (Anthony Nelson, 1995) 30-40.

Per Holck. “The Oseberg Ship Burial, Norway: New Thoughts on the skeletons from the Grave Mound.” European Journal of Archaeology 9.2-3 (2006)185-210.

John Hale. “The Viking Longship.” Scientific American, Feb., 1998. (note Hale also did his Cambridge Ph.D. on Viking ships).

Patrick Hunt “Viking Legacy” Humanities West Event, Age of Vikings: Wanderlust, Viking Raiders, Traders, Neighbors, February 24-25, 2017 (http://humanitieswest.net/wanderlust-793-1066-viking-raiders-traders-neighbors/).

Judith Jesch. Ships and Men in the Late Viking Age: The Vocabulary of Runic Inscriptions and Skaldic Verse. Martlesham, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer Press, 2001.

Barbara M. Kreutz. “Mediterranean Contributions to the Medieval Mariner’s Compass”, Technology and Culture 14 (1973) 367-383.

Viking Ship Index (http://www.vikingskip.com/vikingshipclasses.htm), most recent update 2015.

Anna M. Rosenqvist. “The Stabilizing of Wood Found in the Viking Ship of Oseberg, Part II.” Studies in Conservation 4.2 (1959) 62-72.

Roskilde Vikingeskibs Museet (Roskilde Danish Ship Museum) http://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/

Mark Strauss. “Discovery Could Rewrite History of Vikings in New World”, National Geographic News, March 31, 2016 (http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/03/160331-viking-discovery-north-america-canada-archaeology/).

Snorri Sturluson, Heimskringla (partly the Saga of Olav Tryggvason) 13th c., translated by Samuel Laing, 19th c.