By Andrea M. Gáldy –

Das Konstanzer Konzil. Weltereignis des Mittelalters 1414-1418. Grosse Landesausstellung 2014 im Konzilgebäude Konstanz (27. April – 21. September 2014), organised by the Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe.

Karl-Heinz Braun, Mathias Herweg, Hans W. Hubert, Joachim Schneider und Thomas Zotz, eds. Das Konstanzer Konzil. Catalogue and volume of 65 Essays. Theiss, Darmstadt, 2013, pp. 400, 500 colour plates, €49,95.

600 years ago the Christian world gathered at the shores of Lake Constance. After the papacy had returned to Rome from its Babylonian Captivity at Avignon (1309-1377), the next potential affliction arose in the guise of the Great Schism. From now on until the election of Martin V (Otto Colonna, Fig. 2) on 11 November 1417 more than one pope tried to rule over Catholic Christendom. When Gregory XI died in 1378 in Rome, the archbishop of Bari was elected as his successor and took the name of Urban VI. The new incumbent was, however, not universally acknowledged and an anti-pope was elected by the French faction; he returned to Avignon with a rival papal court under the name of Clement VII. The schism split Europe into two political camps: about half declared for the Roman pope and the other half (among which Castile, Aragon, France, Scotland, Naples and the Holy Roman Empire) for the Angevin candidate. Thus an ecclesiastical crisis managed to turn into a political rift which proved more long-lasting than earlier, temporary anti-papacies would have led one to expect. Indeed, so deep went the split that even the death of Urban and Clement did not put an end to this unfortunate situation but continued with a new set of rival claimants well into the new century. Several remedies were tried to solve the problem but none were successful; a council convened at Pisa in 1409 only resulted in the election of a third anti-pope, John XXIII.

It was precisely this Pisan pope (Baldassarre Cossa, c. 1370-22 December 1419), eventually buried in the Florentine Baptistery of San Giovanni in an elegant tomb monument by Michelozzo, who eventually called for a church council at Constance. All three popes – the Roman Gregory XII, the Angevin Benedict XIII and John XXIII – met during a global event that attracted delegations from as far away as Ethiopia, Crete, Constantinople, the British Isles and Poland-Lithuania and brought up to 70,000 visitors into the city which was trying to cope with difficult and unforeseeable logistics as well as a very diverse group of religious tourists over the course of four years. In the end, the Roman and the Pisan claimants abdicated while the Angevin incumbent was forced to retire, ensuring the possibility of a conclave which took place over four days in a trade Emporium on the shores of the lake (Fig. 3). Even though John XXIII seems to have counted on a considerable majority, in the end his gamble of convening the council did not pay off. Otto Colonna was the successful candidate and, despite a number of antipopes being elected in the council’s direct aftermath, led Roman Catholic Christianity back to unity for the time being. Martin V even found the magnanimity to appoint Cossa as cardinal bishop of Frascati, although he allegedly criticised the inscription on Cossa’s tomb which called John XXIII a “former pope”.

By the time the council took place the necessity to reform the Christian church had become quite obvious. Eventually, this need was going to lead to the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-reformation of the following century. But even in the early fifteenth century as the result of decades at Avignon and of the Great Schism considerable criticism was raised against abuses current in the established church: for example nepotism, simony and the trade with indulgences. Critics were more often than not labelled as heretics and paid for their intrepidity with their lives. Perhaps Jan Hus (1369-1415), theologian, professor and rector of Prague University, thought that he had a fighting chance when he followed the “invitation” to explain his ideas to the Council, perhaps he tried to protect Prague and the Charles University. Despite the safe-conduct he had received from Sigismund of Luxemburg (1368-1437), king of the Romans and as interested in a successful Council as was John XXIII, Hus was arrested, imprisoned and treated so badly that his health started to fail very quickly. When he finally got a hearing, he was unable to defend his position. Not – one gets the impression – that anyone took a great interest in what he had to say. Although Hus was killed at the stake in 1415 (Fig. 4), his thoughts remained influential. He was revered by his followers and his garment was preserved as a relic; part of it is displayed in the exhibition (Fig. 5).

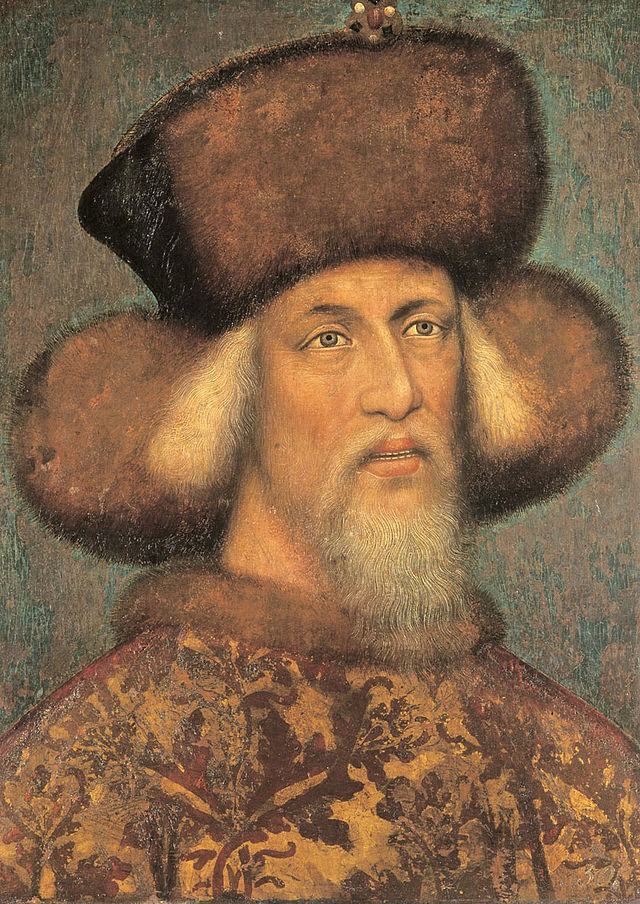

King Sigismund (Fig. 6), king of Hungary through his marriage to Queen Mary, had been elected as king of the Romans in 1410 and again in 1411. After years of internal often violent opposition as well as warfare against the approaching Turks, he hoped to secure his position as Holy Roman Emperor. A papal coronation was required: with two or sometimes three popes in office contemporaneously, it was of vital importance to make sure that the coronation ceremony (31 May 1433) was conducted by the one real incumbent. Hence, Sigismund’s interest in the Council, even though he took notice of the need for reform and had indeed instituted a law, called the Placetum Regium, according to which papal bulls did not become valid in Hungary until they had been approved by the king. He attended the Council and also took an active part in the events, for example by reading out the gospel during mass at Christmas, a privilege he held as emperor elect and thus in reference to Augustus and Charlemagne.

The Council of Constance was only one link in a chain of such ecclesiastical events aimed at unifying the Roman Church and at uniting it with the Eastern Church, not least under the impact of the Ottoman invasion into Europe. In 1438, after Sigismund’s death, Pope Eugenius IV convened a council at Ferrara which was later moved to Florence (1439). At its conclusion in 1445 the Greek Church had made dogmatic concessions in return for military help against the Turks. The agreements were short-lived and Constantinople was conquered by the troops of Sultan Mehmed II in 1453.

There is no doubt that the Council of Constance, for all its intrigues and missed opportunities was an event of high importance with a long-lasting impact on European ecclesiastical history and secular politics. It brought together a large number and international group of humanist scholars, artists, politicians and clergyman for four years who exchanged gifts and ideas and enjoyed the hospitality of the Council’s location, not all of it exactly highbrow (Fig. 6), as well as the vicinity of first-class monastic libraries in which Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459) and his colleagues might discover untold literary treasures. Therefore, the exhibition organised by the Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe which brings together exhibits from museums across Europe cannot be praised too highly, in particular since it includes sights in the city of Constance as well as themes and displays which go beyond the usual expectations in a religiously themed exhibition. In twelve sections, perhaps a bit too crammed for comfort, the exhibition explored the religious, geopolitical as well as scientific situation in 1400s Europe and gave much attention to the diverse achievements of the figurative arts. An event such as the Council acted as a huge trade fair: conspicuous consumption and diplomatic gifts acted as catalyst for the exchange of the latest artistic trends. Many different styles were in fashion at the same time during the first half of the fifteenth century, ranging from icons allegedly repeating the portrait of the Blessed Virgin as painted by St. Luke, over Madonnas in the “beautiful style” in a garden setting evoked by the monastic garden recreated outside the council building to initial experiments with one-point perspective and greater individuality and naturalism in the depiction of human sitters.

The exhibition is well worth a visit and guided tours are available in German, French and English. Strangely though for an event celebrating such an international occasion and with objects on loan from a large number of European countries, the cards in the exhibition as well as the catalogue are composed solely in German. Surely, the (at least) European scope of the project ought to have prompted a more cosmopolitan arrangement. Incidentally, during the fifteenth century the language problem was felt as well: the “blogger” of the Council, Ulrich von Richenthal (d. 1438) wrote in the local German dialect but at least one manuscript version of his richly illustrated chronicle (Fig. 1) was translated into Latin.