By Patrick Hunt –

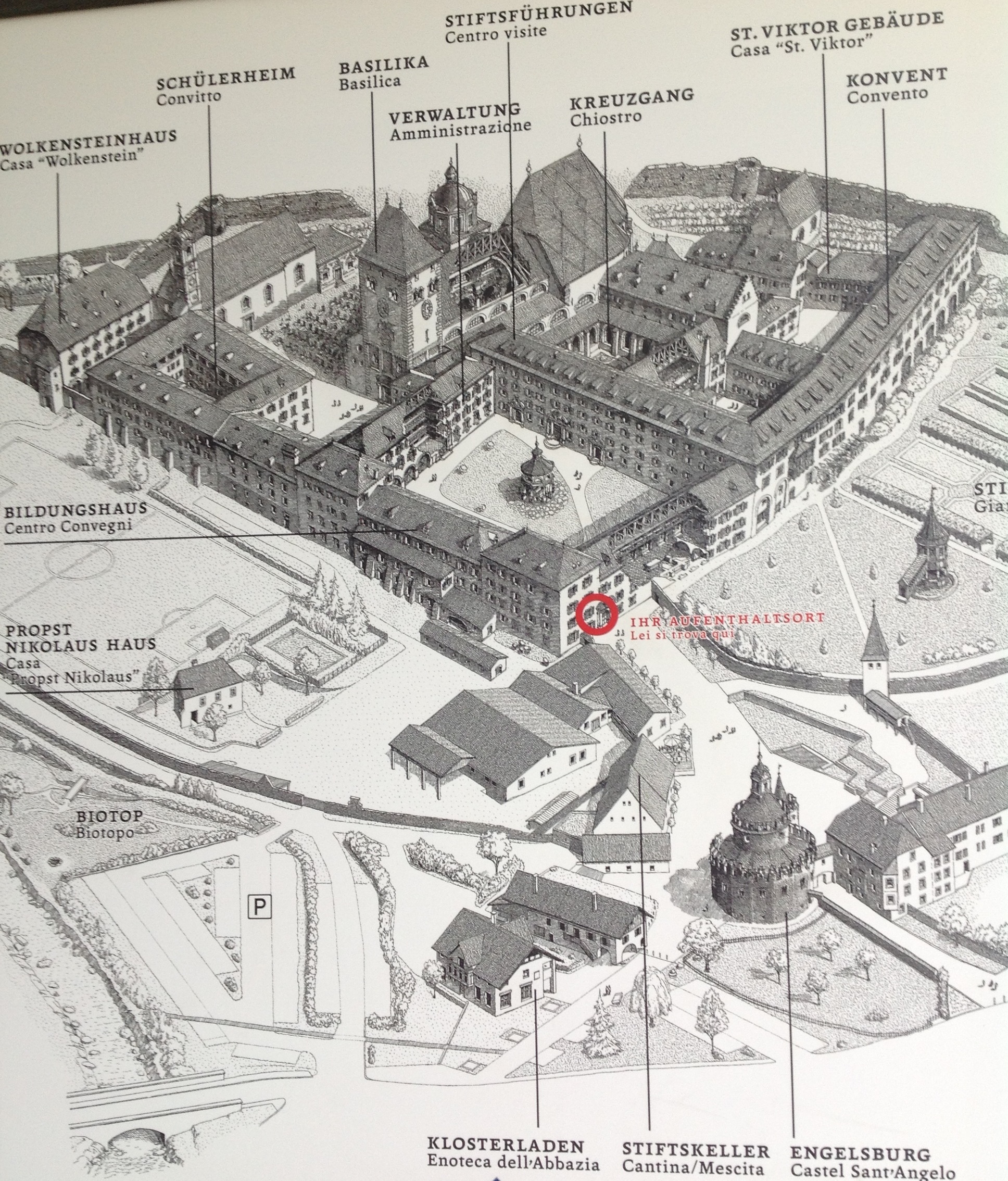

The Abbazia di Novacella is in the South Tyrolean municipality of Varna (Varhn), surrounded by its monastery vineyards above the Isarco (Eisack) River. South Tyrol was part of Austria until 1919 but is now Italy. The Abbazia is steeped in history, from its medieval foundation around 1142 to its Baroque embellishments. In the courtyard is a roof-covered well whose upper frescoed panels depict the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, in some way fashioned after the new encyclopedic vision of the Renaissance. Also known by the German speakers of South Tyrol as Kloster Neustift or more formally as Augustiner Chorherrenstift because it was known for fine singing since the fifteenth century, this Augustinian abbey is equally famous today for its fine wines. A visit for wine tasting in its cellar (Stiftskeller) and seeing the range of wines in its enoteca will be satisfying for anyone thirsty for historic wines of the Alto Adige, varietals like Kerner and Sylvaner as well as Veltliner, Lagrein and Gewurztraminer (Traminer is a town south of Bolzano near Trento after the Eisack River flows into the Adige).

Both the modern plan of the monastery and the actual buildings themselves also show architectural conflation as the Augustinian Canons adapted to changing world tastes. The old basilica interior has been thoroughly transformed into an almost Neapolitan Baroque and the round Engelsburg (Castel Sant’Angelo) is a fusion of medieval and Renaissance. Although Athanasius Kircher (1601-80) did not write specifically about each of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, [1] if his academic legacy here as preeminent Vatican Scholar of the 17th century is only part of a parochial world ready to embrace achievements of ancient civilization, what better way to acknowledge the past than to represent the Seven Wonders here?

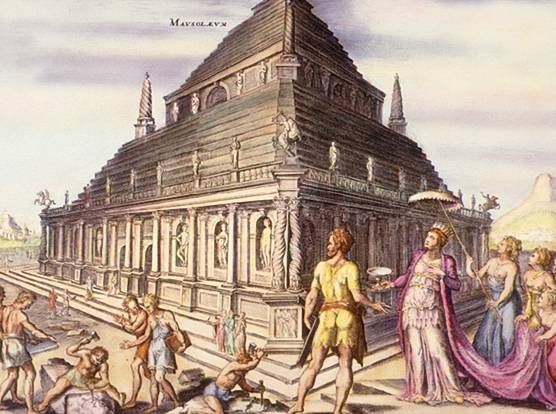

But the clearest influence on the Abbazia fresco panels on the well – possibly antedating Kircher – are the considerably earlier Mannerist engravings of Maarten van Heemskerck (1498-1574) for Philip Galle in 1572, and the most derivative arcaded well panels are those of Heemskerck’s Mausolaeum (of Halicarnassus), Dianae Ephesie Templum, Colossus Solis (of Rhodes) and Babylonis Muri in that order, although his Pharos (of Alexandria), Pyramides and Olympe Iovis Simulacrum are also sources for these South Tyrolean versions. Because the Abbazia well has an octagonal roof, an eighth panel is needed, filled with a monastic exemplum. The decorated fresco series around the octagon have hues mostly emphasizing blue in the sky and gold in their architectural elements, including Atlantid figures on the edges appearing to hold up the acanthus leaf torus. The Seven Wonders panels start with what are described and depicted as Iupiter Olympius, continuing to the right with the Pharos, then moving to the Pyramides and Murus Babyloni and on to Mausolaeum, Diana Templum and Colossus. Some of the Austrian Renaissance artists who worked for the Augustinian Canons here include the Master of Uttenheim (flourishing around 1470), local artist Michael Pacher (ca 1435-98) from nearby Brixen (Bressanone) and Max Reichlich (1460-1520), although the Seven Wonders panels are not of their high quality.

The Iupiter Olympius panel begins the Seven Wonders series at the abbey’s courtyard well, as seen here. Jupiter holds a thunderbolt in his right hand, seated in the apse of an open temple. The original Phidian Zeus sculpture inside the temple designed and built by Libon at Olympus was a marvel in god and ivory (chryselephantine) about 43 feet tall. The statue was seated because that was an attribute posture of the chief Greek god and also because the Olympian temple height would not have been able to support a standing Zeus of equal majesty. The technology of large-scale ivory in layered sheathing over a wood frame and use of gold for inanimate parts of the sculpture on such colossal ancient figures was only recently extrapolated from Pliny in the past decade. [2]

The Pharos is the Lighthouse of Alexandria, although the Library of Alexandria was a symbolic lighthouse on its own for the ancient world, representing literacy and the illumination of knowledge including science, literature and philosophy. Estimates of its papyrus scrolls in the original library range up to 700,000 scrolls. The lighthouse in the harbor whose foundations are still visible could be seen for many miles to sea, necessary to avoid shoals in the shallow water of a very flat African coast, being over 400 feet high. Its light must also been burning at night and possibly enlarged by mirrors. The last remnants stood until the 14th century.

The Murus Babyloni (Wall of Babylon) show the Herodotean 5th c BCE story rather than the later Hanging Gardens, most likely in Assyrian Nineveh, not Babylon, according to Stephanie Dalley [3] from the Hellenistic list of Antipater of Sidon. Herodotus says the walls were built by Semiramis, a legendary queen whose husband is most often recorded as Assurbanipal, king of the Assyrians.

The Pyramides panel shows a landscape with hyper-extended narrow pyramids more typical of Meroe and the upper Sudan than Giza, almost obelisk-like in form but several with bright red hues. Giza has two large pyramids – Khufu’s and Khephren’s – and the smaller Menkaure one, likely suggested here by the larger pyramids in both Heemskerck and this panel.

The Mausolaeum panel recalls another Hellenistic monument, its original a compendium of Lydian, Greek, Egyptian and possibly Persian elements. The original 145 feet high tomb of King Mausolus, a satrap client king of Persia in the mid-fourth century BCE in Caria of western Anatolia, was built by his stricken wife Artemisia after his early death; her clever assumption of the reins of power for years was partly due to her famous act of love: she mixed his ashes in a drink and consumed them so that she became the real tomb of her royal husband. She also hired the best Greek sculptors of the era to decorate the monument: Timotheus, Leochares, Bryaxis, and Scopas, among others.

The Diana Templum panel celebrates one of the largest Greek temples of all time, the Artemision of Ephesus as it was known in the Greek world. The Great Goddess was an old Anatolian fertility deity whom the Greeks identified with the Potnia Theon or Mistress of Beasts, flanked by wild animals including stags and other animals like great felines and bulls. One ancient version often has the torso of Artemis adorned with votive amber gourd shapes. although many since antiquity have erroneously identified these as eggs, breasts or even bull testes. The great Greek temple – one of at least six built on the site, each over the ruins of the other – was likely over 100 feet tall with 127 high columns at least 60 feet high and its base was around 377 long by 155 feet wide. A myth of destruction for the Classical temple was that it burned down on the day of Alexander the Great’s was born because Artemis was away in Macedonia tending his birth instead of protecting her Anatolian domain, according to Plutarch (Life of Alexander 3.6-7), who also suggested that it was prophetic for the Magi who hinted that the event would cause further disaster for Asia: not only the Artemis temple destruction but the destruction of the Persian Empire (through Alexander).

The Colossus of Rhodes panel suggests a giant bronze man as a representation of the sun god Helios standing over the harbor of Lindos Rhodes, and we now know ships would not have passed between its legs (as depicted here from Heemskerck), since if it stood about 100 ft tall, its stance would not have been spread wide enough to allow ship passage. The block it stood on was 50 ft high, making the total monument about 150 feet high. Finished by Chares of Lindos around 280 BCE, it should stood for no more than 56 years, destroyed by earthquake around 226 BCE. Ancient sources including Strabo (1st c BCE to 1st c CE) and Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) describe it lying down as a broken wreck by the harbor. In the seventh century CE after the Moslem Conquest the bronze wreck was sold to a merchant of Edessa who needed 900 camels to transport away the bronze pieces. The Statue of Liberty in New York harbor is a modern imitation and even the Emma Lazarus poem on its base recalls the Colossus of Rhodes in its “brazen giant of Greek fame”.

The Heemskerck original engravings that Philip Galle published around 1572 show how derivative these frescoes are, especially obvious in the Dianae Ephesie Templum and Mausolaeum images here:

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were not only “marvels” (thaumata), but also things “to be seen” (theamata) by great travelers or locals as well, a bucket list of antiquity. [4] Although the fanciful representations of Heemskerck copied by the fresco painter here at the Abbazia di Novacella are unrealistic, these images of the Seven Wonders of antiquity show a monastic fascination and curiosity for a larger world of science and knowledge despite the constraints of a cloistered context.

Notes:

[1] Paula Findlen. Athanasius Kircher: The Last Man Who Knew Everything. Routledge, 2004, 175, (Hanging Gardens), Egyptian pyramids as “tallest monuments” (338).

[2] Kenneth Lapatin. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Oxford University Press, 2001.

[3] Stephanie Dalley. “Nineveh, Babylon and the Hanging Gardens: Cuneiform and Classical Sources Reconciled.” Iraq: Journal of British Institute for Study of Iraq 56 (1994) 45-58.

[4] Peter Clayton and Martin Price, eds. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Routledge, 1990 repr., 4.