By Patrick Hunt –

The Order of the Golden Fleece in late medieval Europe found its source in the old Greek myth – at least as old as Homeric lore – of the hero Jason’s search for the Golden Fleece. This magical ram fleece of pure gold itself recalled an earlier tradition – with a grain of historical truth – of collecting riverine placer gold washed down from Anatolian mountains by placing a thick wooly fleece at a point in a stream bearing gold where the nuggets or gold dust would be trapped in the curly wool. The tale is best told in the third century BCE by Apollonius of Rhodes in his Argonautica in Alexandria. Another brief episode can be found in the poet Pindar’s Fourth Pythian Ode (circa 460 BCE). The most consistent location for the Golden Fleece in Greek myth was in Colchis. In the Greek myth, however, Jason needs either the magic of his lover-witch Medea or the aid of the goddess Athena to obtain the Golden Fleece, the golden ram skin hanging from a tree but guarded by a serpent or dragon.

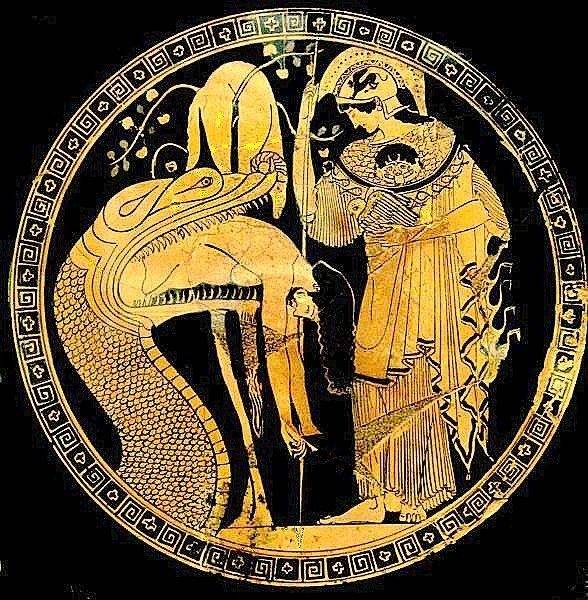

One famous Greek vase in the Vatican apparently painted by the artist Douris in the fifth century BCE (circa 475 BCE) depicts a variant of the Greek myth not found in the literature, as seen in the illustration (Fig. 2). We have no other surviving literary or artistic examples of this ancient Greek telling of the myth where Jason dies or is regurgitated from the dragon and must be resurrected by Athena. On the right is the goddess Athena in her role as protectress of heroes. On the left is the giant serpent dragon with a possibly dead and seemingly wet Jason hanging from its mouth. In the left background behind the dragon is the small tree with the ram fleece also hanging in parallel symmetry to Jason. Here it is the power of the goddess, with her spear planted in the chthonic earth, that both divides the scene between human and monstrous elements and the Olympian world of powerful deities who intercede on behalf of humans. In some way, this ancient myth of divine connection and the fleece as a symbol of both human endeavor – Jason in search of the magic fleece – and divine blessing mediated by the goddess of wisdom connects to the European order envisioned by its French founder, Duke Philip III the Good of Burgundy.

In 1430 the Duke of Burgundy, Philip III the Good, borrowed the tradition of the Golden Fleece from Greek myth. He and his high officers founded an order of knighthood based on the challenging precedent of obtaining such a golden fleece by heroic will aided by divine power. One of the events associated with the founding of the order was Philip’s wedding to the Princess of Portugal, the Infanta Isabella in the same year.

Starting in Bruges, Philip as grand master of the order instituted this noble order by naming 23 knights to its ranks, their primary prestige coming from first being able to prove impeccable noble ancestry and second from their oath to defend the faith [1] and furthering chivalric ideals and third from their to the Duke of Burgundy (which may have been after all the real purpose). The last goal also inevitably embroiled the knights in politics because while they were assumed more trustworthy if they were above bribery, the prestige associated with the order made the gamble of being deemed unworthy (corrupt based on ends justifying means) worthy of risk. It was not that knighthood was any less pragmatic than another great challenge as much as the candidates were assumed to be of the best breeding if one could satisfy all the conditions, most important of which was an unassailable, near endless genealogy of noble ancestry. It was also probably more important that the knights were the Duke’s team players than if their rosaries might be slightly tarnished or not quite as holy as expected. Although as mentioned the original number of knights was 23, it soon grew to 31 and was then fixed thereafter at 51 (currently about this number in 2012).

While Duke Philip founded the order in Bruges in Flanders, its first chapter was in Lille and within two years (1432) its original French administration moved permanently to Dijon, the ducal capital. Vicissitudes of war, territorial changes and family divisions within the various European realms – especially within the fragmentations of the so-called Holy Roman Empire and the absorption of duchy of Burgundy into the kingdom of France – ultimately witnessed the establishment of the Order of the Golden Fleece under the Hapsburgs first in Spain and then Austria. Descendants and newly minted knights have continued the order’s traditions, especially not allowing heretics, although even after the Reformation in the 16th century, Protestants have not been represented in its ranks. The order is still active, however diminished, in Austria as well as other parts of Europe, mostly in remnant noble houses in France and Germany, although the order’s seat is Austria where the Hapsburgs mostly ruled. Although it is rare for modern member knights to come from outside the traditional aristocracy of long-standing families, a notable current exception has been French President Nicolas Sarkozy (as elected co-ruler of Andorra). On the other hand, as one of the few ruling monarchs in the world and from an old Hapsburg family, the Prince of Liechtenstein is one of the highest ranking living noble members of the order. The two surviving branches of the Order of the Golden Fleece are Spanish and Austrian.

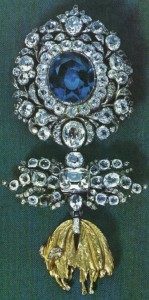

The medallion of the order has changed over time from the Burgundian to Hapsburg branches but the visual image has always retained the pendant of the limp fleece held around its middle by a belt. The order’s insignia is generally made in gold – sometimes resplendent instead in diamonds – and often decorated with many colored gems and enamel, as in the Dresden Green Diamond. The Wittelsbach Family, with many members belonging to the Order of the Golden Fleece, and others like royalty could mount enormous sapphires or other stones as emblematic of their wealth and power.

For cachet in the nineteenth century, the American New England-based clothiers Brooks Brothers adopted the embroidered insignia of the golden fleece as a small pendant only attached to the cloth and it still remains the company logo despite efforts of the surviving order to litigate against its borrowing by American non-nobility, although for a few years in recent past, the clothing line was owned by British holding company Marks & Spencer. Europeans usually wonder if Americans actually understand the matter of old pedigree associated with the Golden Fleece, especially when mass-produced as a logo.

Understanding the history of a late medieval order associated with the highest nobility can be tricky, especially in a modern country and culture where aristocracy is only a memory. Hapsburg Emperors like Joseph II (1741-90) are almost always shown in court paintings decorated with the Order of the Golden Fleece, in an above photo where the pendant insignia is shown over his red and white Austrian sash.

In old Heidelberg, along the Hauptstrasse by the University Square (Universität Platz), a little alehouse named ‘To The Golden Sheep’ (Zum Güldenen Schaf) is a reminder that even in a romantic diminution, the Golden Fleece lives on in the magical memory of myth.