By Bianca Caprice Aguirre

C.S. Lewis suggests through his idea of Shadowlands that the world we live in is full of shadows rather than the deeper realities. Although shadows that we see in the world are real and not metaphysical, there is a greater significance to them brought out by Plato in his Allegory of the Cave. Lewis also clearly derived his idea of Shadowlands from Plato’s Republic, as did Neoplatonism as far back as the New Testament Epistle to the Hebrews (8:5) – “a sanctuary that is a…shadow of what is in heaven”. From childhood on we see our own shadows and distinguish them from our true selves. Like the prisoners of the cave, however, we must reach beyond the shadows toward the light; we must enlighten ourselves.

In a modern world still much influenced by the ancient world, it is important to keep an open mind. An open mind makes one open to new ideas, new knowledge, and new opportunities. Even Plato made suggestions of this over 2,000 years ago through his Allegory of the Cave. He describes human beings bound by fetters in an underground cave since childhood. He explains that the shadows that the prisoners see and the echoes that they hear are what they take as true reality. When they are finally freed, and they turn to the true light outside of the cave, they may find it difficult and painful to accept it as the true reality, something truer than what they grew up knowing. Allegorically speaking, the freedom of the prisoners means that their minds open for enlightenment, the highest form of education.

Our word “educate” is derived from the Latin word “ēdūcĕre”, primarily meaning “to lead out.” This definition emphasizes the similarities between leading one out of the cave toward the light, and educating. Enlightenment – as the highest form of education – means to give intellectual or spiritual light to, or to instruct and impart knowledge to. It can also mean to literally shed light upon as was done in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. To stand, turn, walk, and look toward the light after being freed from the shackles in the cave is a great task that not everyone is willing to take, whether out of fear or from the lack of desire to stray from what is comfortable and known. In comparison to the metaphor however, this task does not seem as difficult. Perhaps it is much easier to be compelled to stretch one’s limbs when they have been freed after years of being stationary than it is to free one’s mind. Whereas the movement of the body seems to be something innate, recognizing that one’s way of thinking or the reality in one’s mind is not the true way or the reality may be much more difficult. By keeping open minds, we may more easily accept new ideas, view things in new perceptions, and ultimately educate ourselves and advance ourselves and our society.

According to the Greek philosopher Epictetus, “Only the educated are free.” This holds a lot of significance in both our world today and in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Today, education is what gives individuals the freedom and opportunity to become and accomplish anything they want. In Plato’s Allegory of the cave, it is through seeing the light – education – that the prisoner is truly freed. In the cave, literally looking toward the sunlight lets the prisoner know of an alternate reality. The prisoner becomes aware that there is something he does not know, and he can then be educated about it. In this way, he is further educated about truth and reality. Allegorically, the concept is similar. The individual who sees the light and the good is enlightened, which is the highest form of education. Plato states that the most important thing is “to see the good; to ascend that ascent” (Republic, 519c10).

Because Plato believes that the enlightenment of the individual is so important, both for the individual and for the justice of the society, Plato expressed that it is the responsibility of the enlightened to return to the darkness in the cave and educate the remaining prisoners. He does not, however, say that the philosophers are meant to educate in the sense of forcing knowledge. Instead, they are to “share their labors and honors” (Republic, 519d5) and govern. At one point Plato actually states “education is not what some people boastfully profess it to be. They say that they can pretty much put knowledge into souls that lack it, like putting sight into blind eyes” (Republic, 518b7). This suggests Plato believes that education is not necessarily easy, that there is more to education than just giving knowledge to people who lack it. The comparison to putting sight into blind eyes is thought-provoking. This is especially true because a number of things can be meant by the term “blind eyes.” Individuals with “blind eyes” may be temporarily blind, may be permanently blind, or may refuse to see regardless of their actual vision capabilities. Thus, Plato could have meant that it is impossible to simply place knowledge in those who are temporarily ignorant, in those who are permanently ignorant, or in those who refuse to move beyond ignorance. Education is not such a simple task in Plato’s eyes. The text implies that Plato believes education is just as much the responsibility of the learner as it is of the teacher. In fact, no teacher can hope to educate without being first educated along the lines of Plato’s cave metaphor. Even today, we must be willing and ready to learn. We receive as much out of our education as we put into it.

Plato claims that the power to learn is in everyone’s soul (Republic, 518c5). He states that there is an instrument in everyone’s soul that “is more important to preserve than 10,000 eyes, since only with it can the truth be seen” (Republic, 527e). This suggests that all individuals are capable of learning through the instruments in their souls, and that while these instruments may be similar to eyes, they are much more important for education. By this belief, it would be fair to assume that Plato expects the individual to use this instrument in order to be educated. Thus, Plato would believe that the freed prisoner would suddenly be compelled to turn toward the light, that is, to be educated.

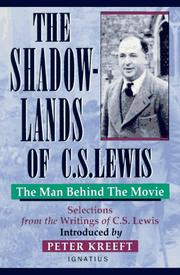

While Plato does not identify what that instrument in our souls might be, we must preserve this mysterious instrument so that we may better ourselves and experience the truer realities of life, exchanging shadows for fuller experience. Although this is only a whimsical point, having lost his shadow, Peter Pan in the J. M. Barrie tale was flummoxed, but we would generally want others we trust to experience our full selves rather than our shadows. After experiencing deeper truth through educating the soul as Plato still encourages, only then can we have the freedom to move towards what is good, to fly like Peter Pan beyond our shadows. Returning to Plato’s mysterious internal “instrument” if we choose to let our instruments lay idle, we will merely be the “uneducated people who have no experience of true reality” (Republic, 519b7). We will not be truly free to do as we please because we will be the uneducated who “do not have a single goal in life at which all their actions, public and private, inevitably aim” (Republic, 519b10). Without a single goal, it is difficult to be compelled to seek the light and what is good, so we must yearn to have open minds and educate ourselves. As C. S. Lewis contemplated Plato’s Cave and the problems of living metaphysically in shadows, in this world we may only yearn to be in that other place where we see “not through the glass darkly” but face to face outside the “Shadowlands” where the light is full.